Monday, April 30, 2007

Continuing with the visualizing fandom line I’ve been harping on recently: several Last.fm users have developed means of taking music-listening data from the site and generating all kinds of interesting things. Many are not visual — they are utilities to compare users’ listening overlaps and divergences, to assess how ‘mainstream’ or ‘extensive’ one’s musical taste is, and so on. See here for an extensive list.

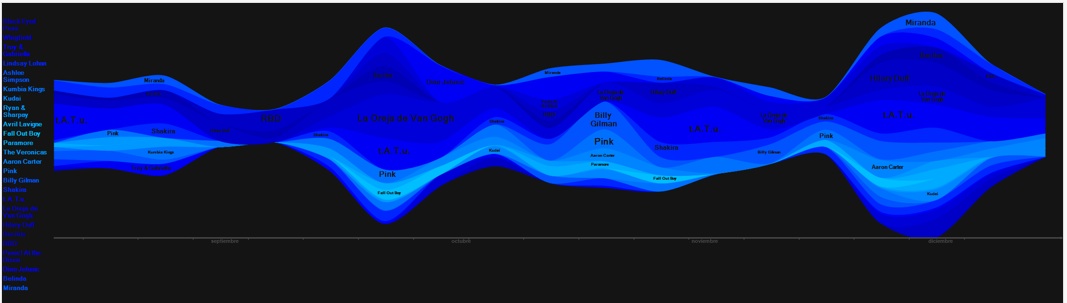

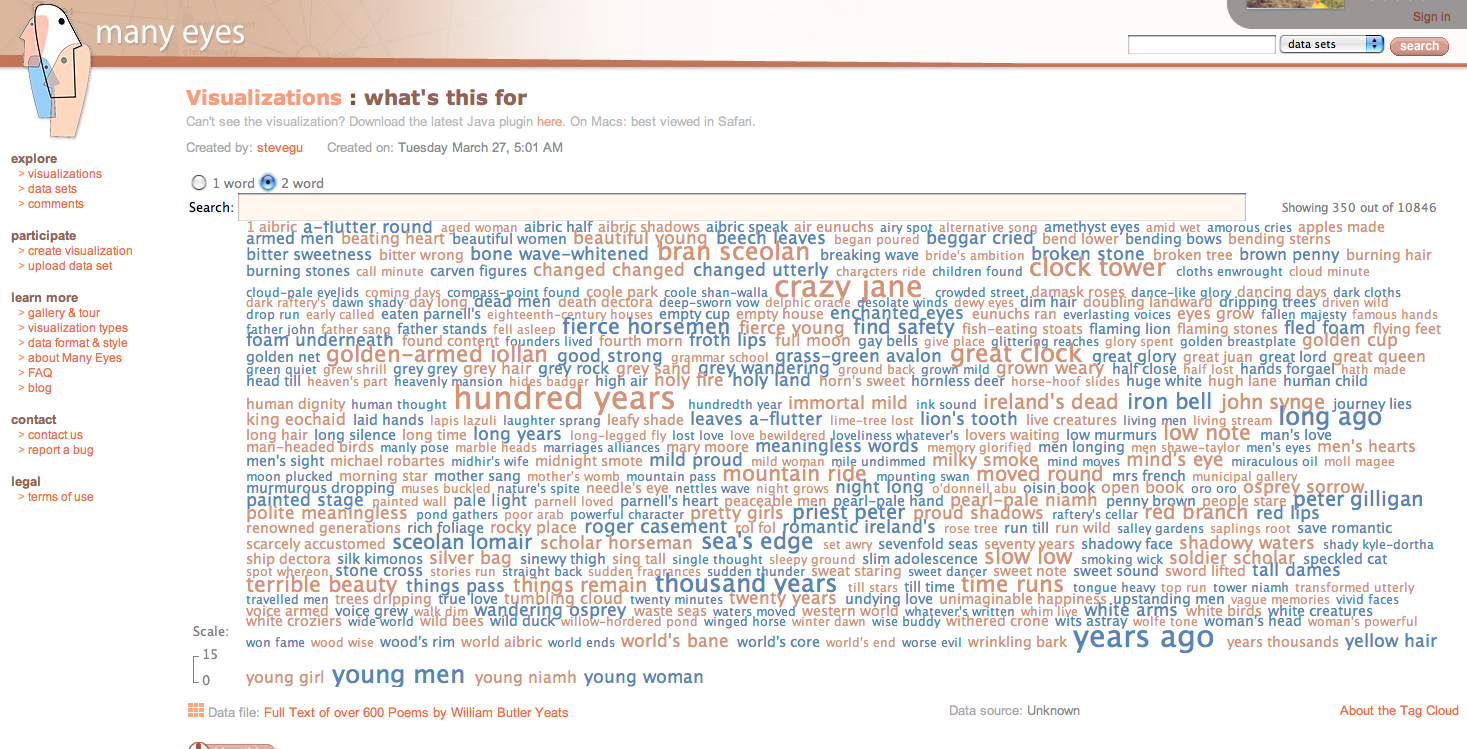

Others demonstrate how visualization can provide really intriguing new ways to look at music. I am completely smitten with this oceanic visual representation of someone’s listening habits over time:

But I can’t make it work for myself as it requires Windows and some other things I don’t have.

I can, however, take advantage of this tag cloud generator that looks at the top user-generated tags for your top artists. It pretty much nailed me (though I’m not sure what that “goodgoing” is all about):

Representations like these can also be generated for Last.fm groups to give an instant overview of communal taste and habits.

This is a truly new way of understanding and communicating music listening (and other elements of fandom) that the internet and, ack, web 2 APIs + user-generated content and applications make possible. Generating statistics and using them to make interesting and sometimes beautiful visual representations may not be for everyone, but I am guessing that online communities would do well to integrate utilities that let people generate visualizations of the data they accumulate, especially when they allow users to compare their own data to group data. Fandom is about identification and play, the more ways we have to represent ourselves through and play with our fandom, the more engaged we’re going to be.

And let’s hear it for the Last.fm fans who are creating these programs. If I ran Last.fm, I’d be trying to get some of these things incorporated into the site instead of leaving it all to clever fans to run on their own.

Friday, April 27, 2007

A deal announced at the MIPTV/MILIA audiovisual and digital entertainment trade show this week looks to merge the online ‘virtual world’ concept with television:

A new virtual world for telly addicts will also be coming onto Internet screens worldwide soon following a deal announced here last week between reality TV giant Endemol and interactive gaming leader Electronic Arts.

Inspired by the runaway success of virtual online worlds, Second Life and South Korea’s Cyworld, the new offering — dubbed Virtual Me — will enable users “to become a star in the virtual world and even take part in their favourite TV shows like Big Brother,” Endemol top exec Peter Bazalgette said.

Endemol’s Virtual Me will let fans create their own personal cyber-clone, or avatar, which can take part in a web-based virtual Big Brother as well as other hit shows like Fear Factor that will launch shortly on the Internet. (link)

There’s a terrific DVD called Avatars Offline in which Janet Murray, an expert in online narrative, argues that Star Wars becoming a multiplayer online game would be the big breakthrough in gaming because the ability to interact with fictional characters in a fictional gamespace one already knew would attract many who wouldn’t want to play Everquest. This DVD was pre-World of Warcraft, which has turned out to be wildly more popular than Star Wars, despite no grounding in well known story worlds.

Cyworld and Second Life are very different stories and it seems a little odd to collapse them. The former is powers of magnitude more popular than the latter — ask a Korean teenager or twentysomething how many people they know on Cyworld, and then ask an American how many they know on Second Life, there’s no comparison between their scale and no reason to think either phenomenon would generalize easily to large audiences running around in virtual Big Brothers.

So forgive me if I think that this initiative sounds a little more like hype rather than something that is ultimately going to get bazillions of people playing in-show. But it’s creative thinking and it’s good to see industries figuring out how to push boundaries of giving fans new ways to engage media and one another. It will be interesting to see how it works out.

Thursday, April 26, 2007

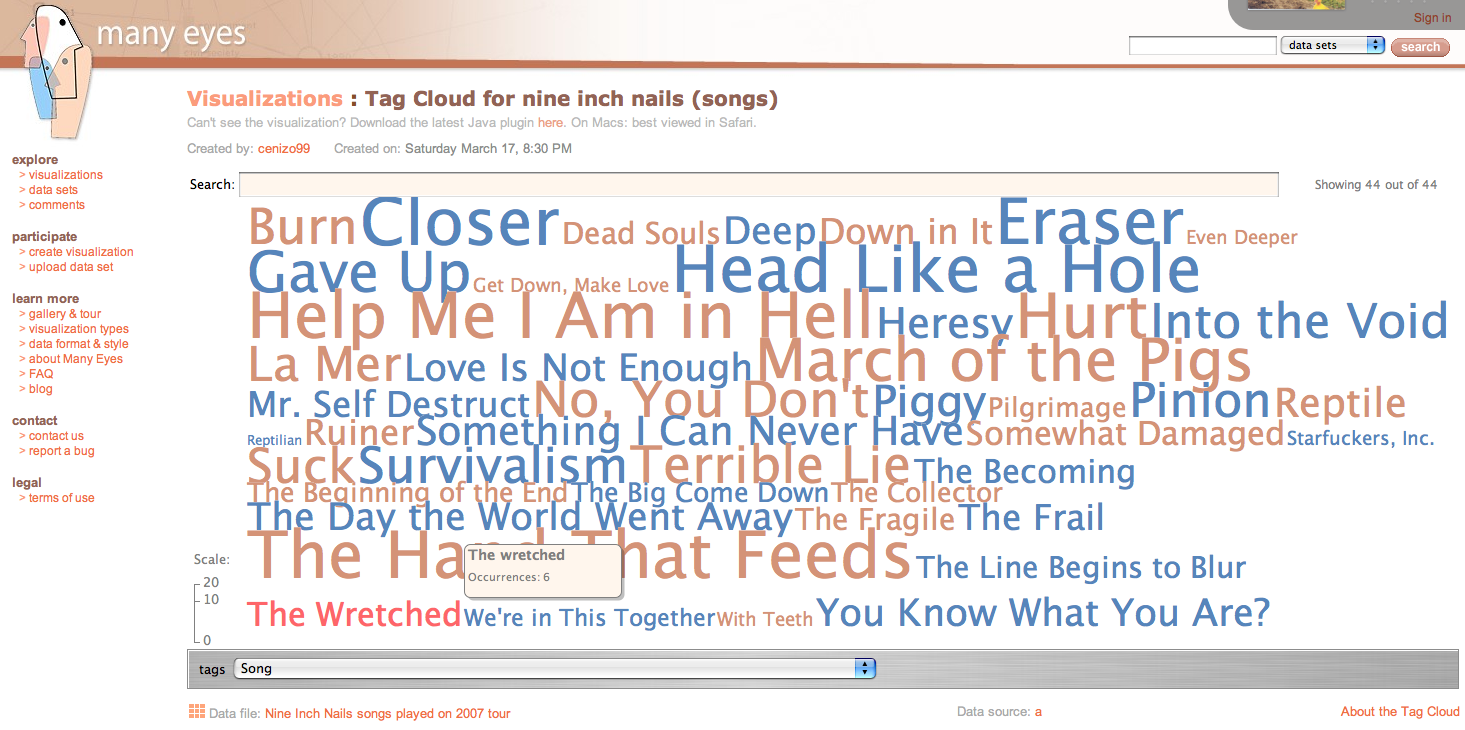

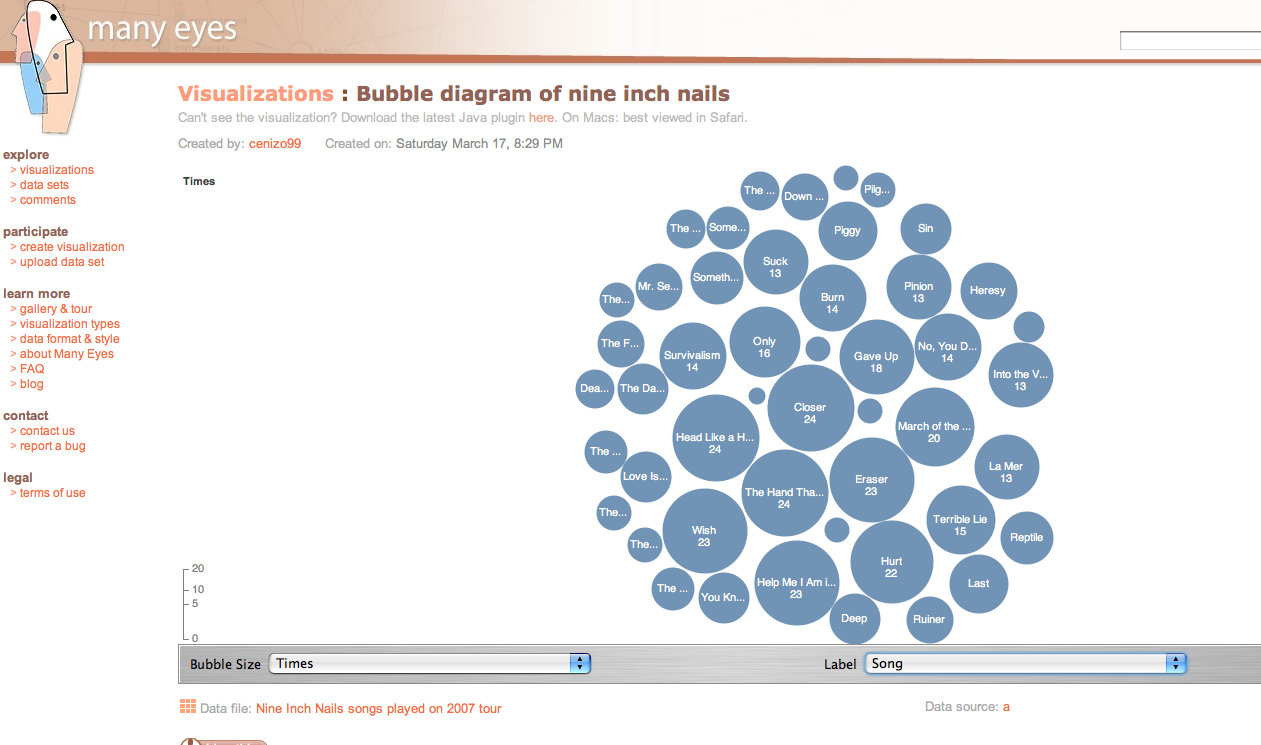

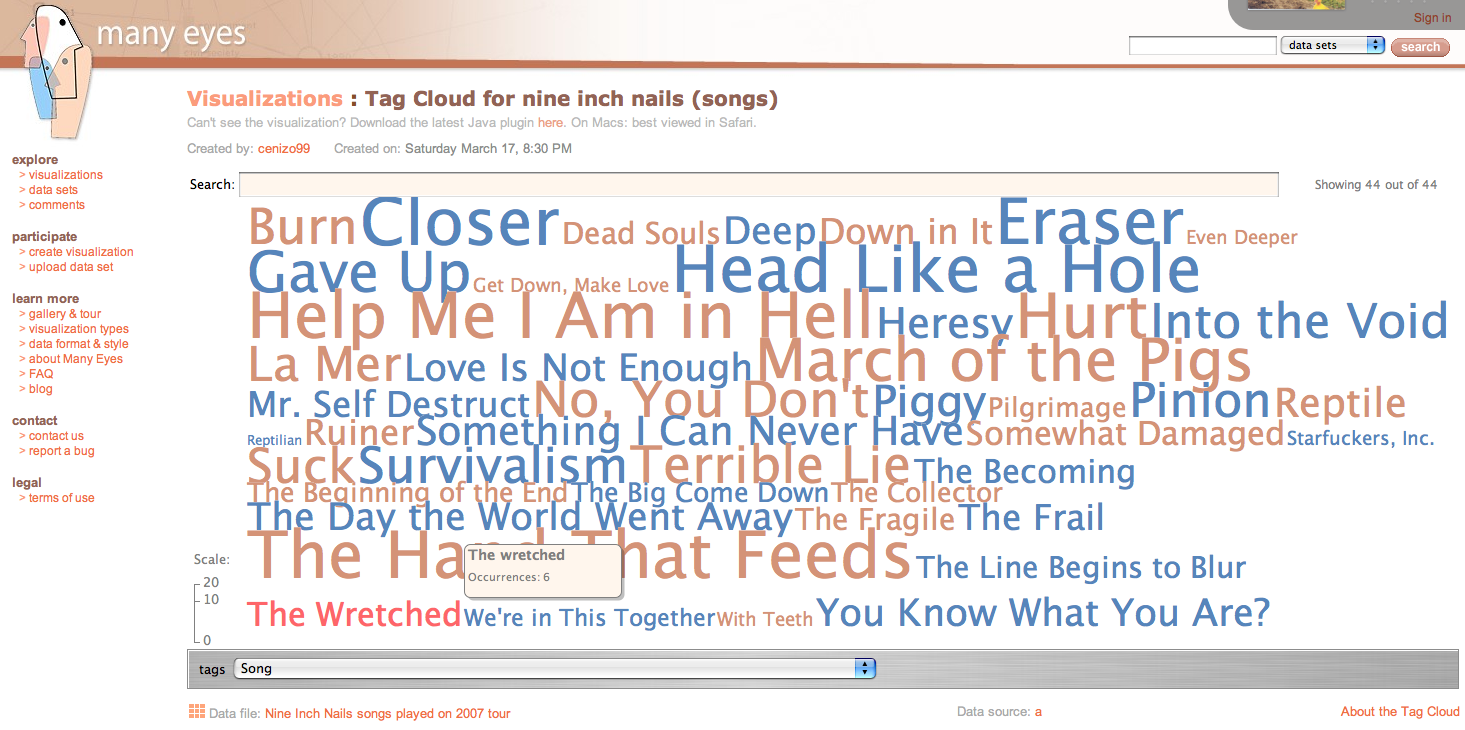

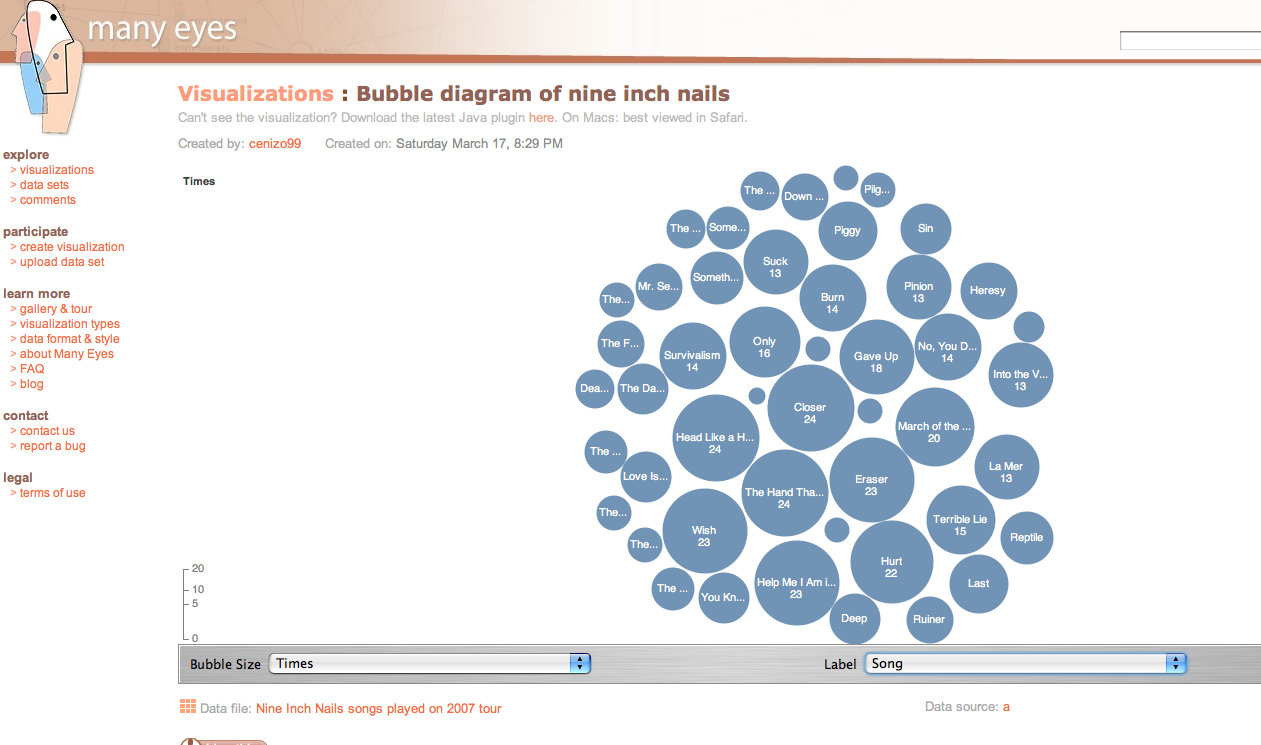

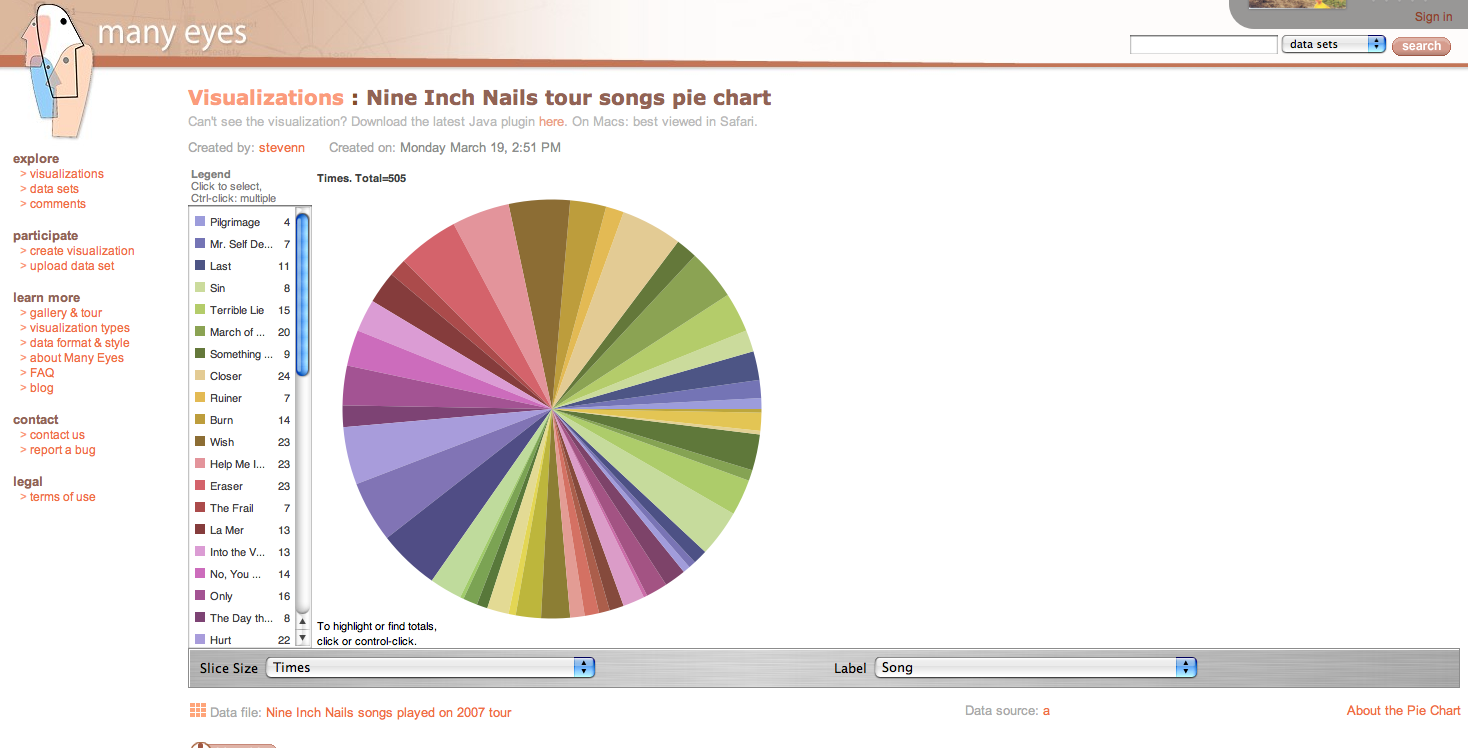

The other day I was encouraging fans to figure out ways to upload information to the social visualization site Many Eyes. Searching around on there today, I found a few compelling examples. Take, for instance, this tag cloud and bubble diagram of the songs Nine Inch Nails played on their 2007 tour (click the images to go to the database and see how interactive it really is — on Macs, it works best with Safari):

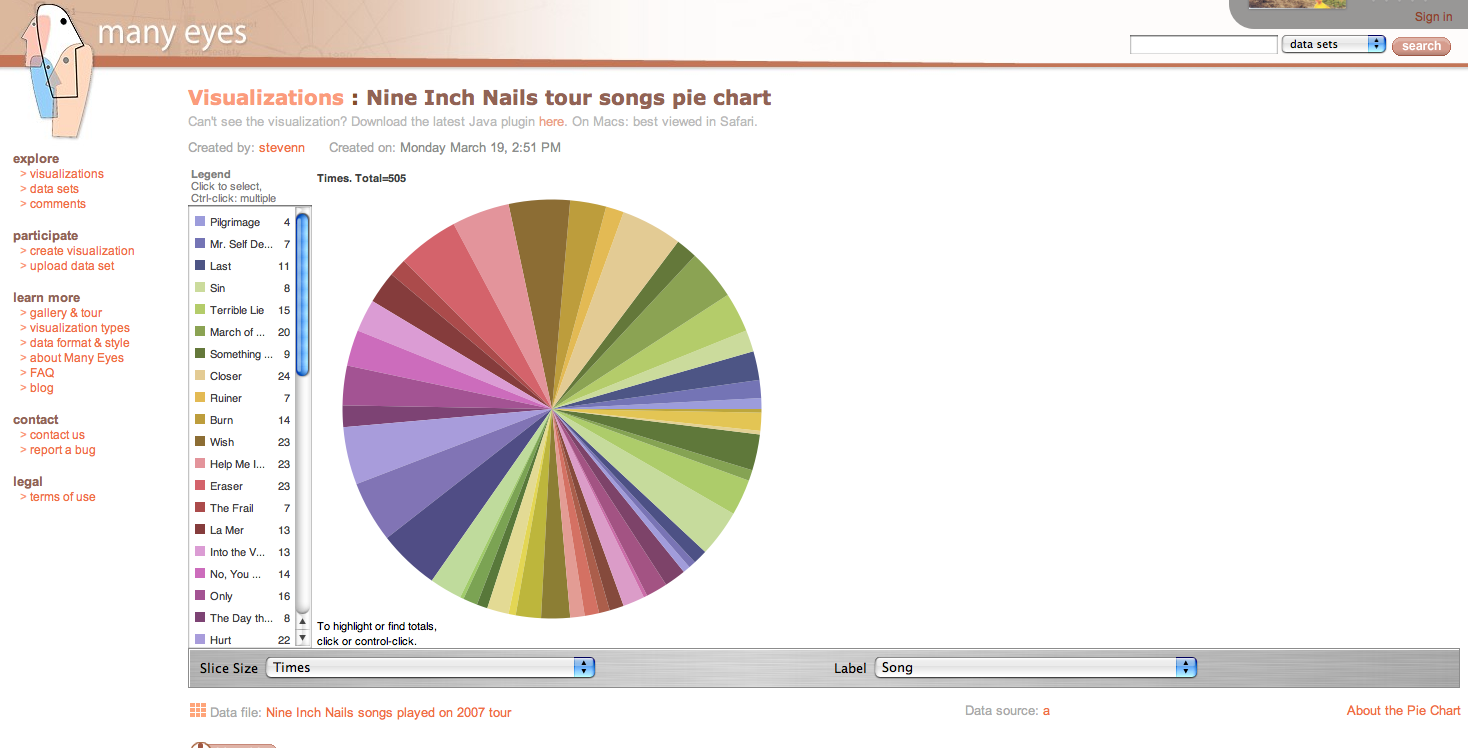

Or did you want that in pie chart form? (you can pull out the slices!)

So just think what you could do if it weren’t just one tour, but all the tours… Makes my fannish heart go pitter patter.

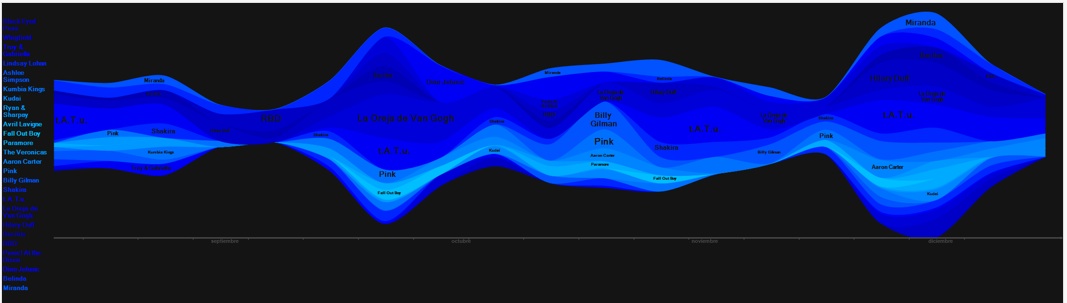

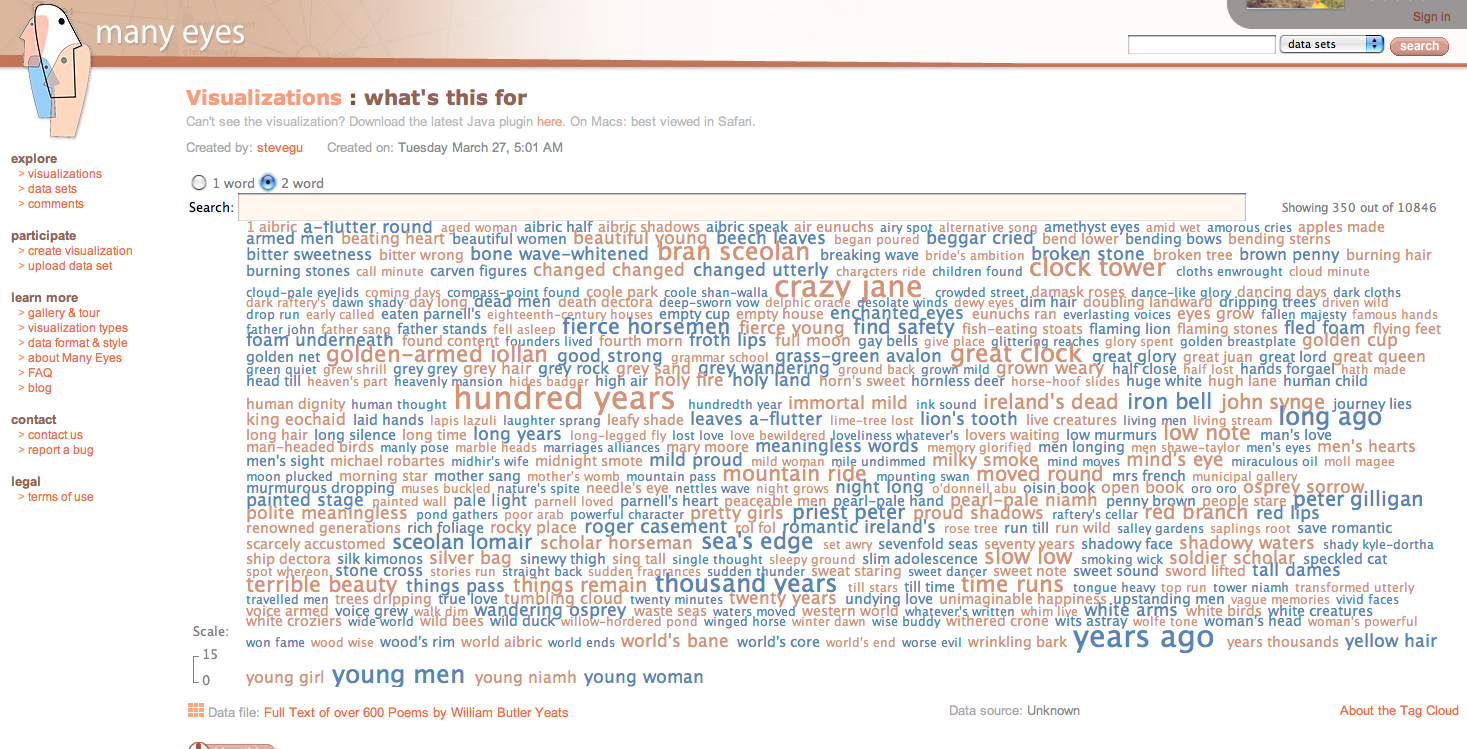

To get a real sense of the potential for instant insight, have a look at this tag cloud of more than 600 William Butler Yeats poems:

How those phrases leap! Hundred years! Years ago! Clock Tower! Long ago! Thousand years! Methinks I sense a motif … Paging Jane Austen fans!

There’s more fan stuff on there, including several very neat social network maps of tv shows and movies (and literature and the Bible, though I’m not sure the latter ought to be cast as fandom). But there ought to be a whole lot more, so start making those databases import-friendly now.

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

At the end of a long and interesting post, Henry Jenkins writes:

C3 research associate Joshua Green and I have begun exploring what we call “spreadable media.” Our core argument is that we are moving from an era when stickiness was the highest virtue because the goal of pull media was to attract consumers to your site and hold them there as long as possible, not unlike, say, a roach hotel. Instead, we argue that in the era of convergence culture, what media producers need to develop spreadable media. Spreadable content is designed to be circulated by grassroots intermediaries who pass it along to their friends or circulate it through larger communities (whether a fandom or a brand tribe). It is through this process of spreading that the content gains greater resonance in the culture, taking on new meanings, finding new audiences, attracting new markets, and generating new values. In a world of spreadable media, we are going to see more and more media producers openly embrace fan practices, encouraging us to take media in our own hands, and do our part to insure the long term viability of media we like.

Indeed, our new mantra is that if it doesn’t spread, it’s dead.

I agree completely that the spreadability of media is essential to its resonance and “long term viability” in pop culture. This struck me as interesting in light of a phenomenon I spoke about at the Cornell/Microsoft Symposium a few weeks ago, which is that online fan groups are becoming less and less place (url/group/mailinglist) based and more and more distributed and nomadic. I used the example of the Swedish indie music fans, who can be found clustering in varied interlinked locations on the net — Its A Trap, SwedesPlease, MySpace, Last.fm, YouTube, and elsewhere. If online fans are not to be found in one or two key spots (MySpace, anyone?), then it’s not just that the media themselves have to come in spreadable pieces, it’s that they have to get into the hands of audiences who are themselves widely spread and often loosely linked through networks of online spaces.

I am not sure about the term “spreadable” which sounds like a highly-processed peanut butter descriptor. Better than “viral,” I guess.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

Does the internet compete with “real life”? This has been one of the (most annoying and) most repeated concerns for about twenty years now, and the answer still seems to be “no.” Digital media are changing our patterns of behavior in important ways, but they are not leaving a decimated trail of old ways in their wake. Some activities we used to do in old ways (watching TV?) may get replaced with an online version (YouTube?), but other things — like having face-to-face conversations and phone calls, hanging out with friends, and taking advantage of community resources like museums and concerts — seem to be either unaffected or slightly increased by online versions of the same.

Now it seems we can add listening to digital radio to the list of online activities that don’t threaten their offline counterparts. According to a study reported in the New York Times:

As a group, fans of digital radio do not listen to traditional radio less than everyone else. In fact, they listen to slightly more, according to a study recently released by Arbitron and Edison Media Research.

The study was conducted through random telephone interviews with 1,925 Arbitron diary keepers, and it lumped together satellite subscribers, recent Internet-radio listeners and anyone who had ever downloaded a podcast.

The data suggest that, generally speaking, fans of digital radio are seeking to supplement, not replace, traditional radio. “Heavy users of digital media don’t think, ‘If I’m doing this more, I’m doing the other thing less,’ ” said Bill Rose, an executive with Arbitron.

This is such a neat parallel to the findings regarding interpersonal communication. And music downloading.

The message I take from this is: Digital radio is traditional radio’s FRIEND, not its enemy. Hurt one, and you may damage the other. Look to work the synergy instead of shutting down the new. Is it too much to hope that this could inform the future of the digital radio licensing fees debacle that seems poised to pull the rug out from under Pandora and every other online radio broadcasting in the U.S.?